7 . 6 . 2010 – I must confess: I wrote this piece with the intention of double-featuring it at Bitmob.com, a game blog developed and ran by industry journalists where helpings of its content is generated by users. Every week a number of posts are hand selected to be published to the front page, and this post was fortunate enough to be one of those last week. They did a nice job editing it and there’s a good amount of participation in the comments, so if you’re curious to read about how other people associate games with times of the year, please visit here.

The sun’s heat reaches over to me as it blasts through the skylights on the other end of my room. It’s already mid-afternoon. I must have taken a nap, but I can’t be bothered figuring how long that’s been for. I’m awake and don’t even realize how much I’m sweating with all the humidity in the air. The taste in my mouth could be best described as a terrible sour hint of orange-juice. Thankfully, no one has eaten me.

It’s summertime, and for the oddest of reasons, zombies are on the brain. Well, not literally. You see, I’ve fallen into a strange and unintentional habit of consuming zombie-lore during massive heat-waves more than any other time of the year.

It all started in the summer of 2002 with the remake of Resident Evil 1 (also known as REBirth, or REMake) for the Nintendo GameCube. My best friend has always been an avid fan of the series, and I distinctly remember him purchasing his very own GameCube for REmake right around this time of year. All we knew was what it was going to look like, and that was enough to be sure the nightmarish memories it left on our childhood would be faithfully recreated as braver teenagers.

I actually had to hold onto the game for him because he was afraid of being distracted from final exams. I suppose knowing a re-make to one’s favorite game is merely a sheet of shrink-wrap away was about as exciting as things got for us back then. Who says younger gamers can’t have their priorities straight?

Not being of age to drive at this point, my older brother took me over to his house on a weekend our friends had set aside for a controller-passing pants-pissing good time. Yet, the most vivid image I have in my head from that entire day, where a television was the only light-source and the surround sound was cranked, is of a giant hot-orange fireball sliding off the horizon on the drive over.

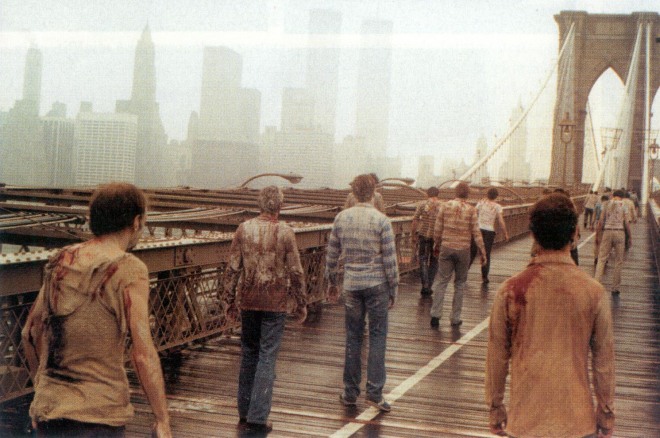

Flash-forward half a decade later to the summer of 2007, when I had just moved into a new house with close friends for roommates. In an attempt to gain a better understanding my new surroundings, I stopped by a local bookstore and wound up purchasing a copy of World War Z. WWZ is a fictional story that recounts the events of a zombie apocalypse from multiple perspectives, via a journalist conducting interviews. It’s a chilling and thought-provoking set of stories that make subtle suggestions about our own societies, and I’d highly recommend that any zombie fans give it a try if you haven’t already.

I remember finishing the book on a balcony when a summer evening couldn’t have been any more pleasant, creating an interesting juxtaposition to the sort of note the book ended on. At the time, I didn’t realize how much of the narrative would stick with me until I got my mind and hands on Valve’s Left4Dead.

L4D actually came out in the chillier November of 2008, but it lasted me far into thawing out of the Spring 2009. It wasn’t so much playing the game though that makes me think of the temperature rising, as it was developing levels for it on a collaborative student project.

A considerable portion of our pre-production took place off-site, capturing reference photography at the local metro parks zoo. Walking throughout the place was surreal. Because we were only just seeing winter come to a close, there wasn’t any dense traffic coming through the parks yet. Large sections of it were under construction, leaving a number of areas in disarray, others completely closed off, and new paths formed to redirect people away from the more dangerous zones. It actually looked like the park had been quarantined and felt abandoned under the more uplifting morning sunlight.

Whenever I think of L4D, my mind always leaps back to that field-trip. At the same time, I can’t see myself ever forgetting how progressively hot it became back in our studio-lab, surrounded by ten foot tall windows facing the sun any moment it was up. To top it all off, Left4Dead2 and its brighter locales only served to further cement my growing paranoia of a zombie-apocalypse happening at any time now.

Enter the present day: rather than help my friend fight zombies, I’m a consulting a short film he’s producing involving them and the social injustice they’re a byproduct of. Just as I was wondering when I’d get my dosage of the walking-dead, it’s already gnawing at my feet.

The larger picture here is how we associate certain video games with certain times of the year in our past, and how that affects our experiences with them, or without them. Sometimes we can so clearly place the rooms we were in, the people we were in the company of, and the general mood our environment made an impression on. I’ll often find myself outside on these summer nights. The desolate streets of suburbia would have me fearing for my brains if a feasting zombie could shamble out from where flickering orange telephone-poles lamps cannot reach. For me, sometimes the summertime is creepier than it should be. Maybe it’s itchy and tasty too.

Have you had any stronger attachments to a game because of when and where you experienced it? If so, take this as an open invitation to share them here.